Note: My team and I didn't end up solving this during the CTF, we got very close though. This writeup goes through the steps I took to finish solving the challenge after the CTF ended. Hopefully you learn a thing or two 😃

1 | Your own secure computer can check the flag! Might have forgotten to add the logic to the program, but I think if you guess enough, you can figure it out. Not sure |

The description seems to hint at something related to "secure computing", and so does the challenge name. Interesting, we shall see.

# Understanding the challenge

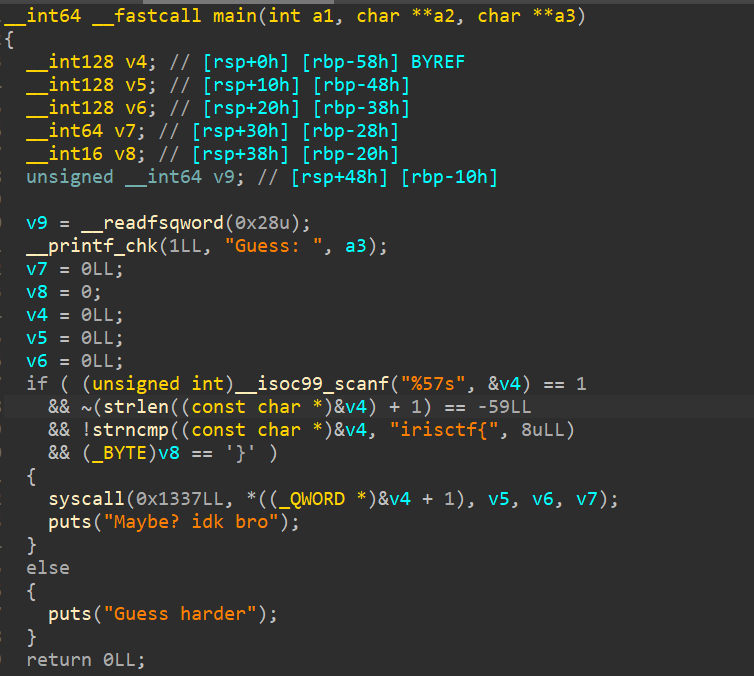

Opening the file up in IDA, we see this

It's passing our input (flag) as arguments to a syscall, in the form of 6 Qwords.

Calling syscall 0x1337 seems a little odd - because it obviously does not exist - so what's going on here?

A quick google search with select keywords seems to point us in a single direction

<br>

The man page of the seccomp syscall gives us this

1 | The seccomp() system call operates on the Secure Computing (seccomp) state |

What does that mean?

# Understanding Seccomp

Seccomp (or Secure Computing) is a security feature in the Linux kernel that provides an additional layer of protection for applications by restricting the system calls that they make. System calls are the interface between user-space applications and the kernel, allowing programs to request services from the operating system.

Some important (and interesting) features of Seccomp:

- It allows you to define a filter that specifies which system calls are permitted for a particular process. By default, all syscalls are allowed, but with seccomp, you can create a "policy" that restricts this set.

- It uses BPF (Berkeley Packet Filter), which is a virtual machine that can execute a set of instructions to filter system calls. Think of BPF as a "javascript for your kernel", because it resides in a VM on the kernel and responds to specific events that occur on the system to which it is attached. The filters are written using BPF assembly or even C, which are then compiled to BPF bytecode.

- It offers mainly 2 modes of operation - strict & filter. In strict mode, the process starts with a seccomp filter in place, and any attempt to make an unallowed system call results in the termination of the process. Whereas in filter mode, the filter is applied only when explicitly requested by the process (we will look at the "how" of this later).

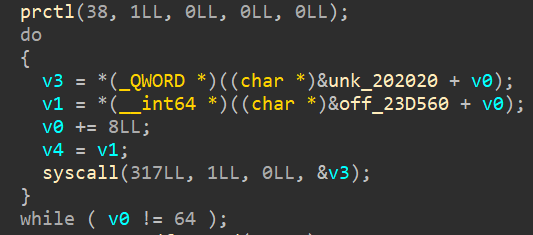

Looking for syscalls with the calling number 317 (seccomp's syscall number), we find this

Hmm, let's look at the arguments passed to it

The prototype of the seccomp syscall looks like this:

1 | syscall(SYS_seccomp, unsigned int operation, unsigned int flags, void *args); |

Here, it seems like operation is set to 1

1 | The system calls allowed are defined by a pointer to a Berkeley Packet |

1 | In order to use the SECCOMP_SET_MODE_FILTER operation, either the calling |

Both of these are being done in our binary. Let us see what the man page says about those BPF instructions containing the actual filters for our input, which will allow us to solve the challenge.

1 | When adding filters via SECCOMP_SET_MODE_FILTER, args points to a filter |

Found our instructions!

So now our approach would be to extract these instructions and disassemble the BPF bytes to see if we can make sense of the filter and reverse it. But let's see if any tool exists that can already do it for us, just to make our lives a little easier 😃

Another quick google search leads us to seccomp-tools, something that exactly matches the description of what we're looking for.

To extract the filters from the binary, we simply run:

1 | seccomp-tools dump ./chal |

But doing this yields no result, why's that?

Reading the GitHub page of seccomp-tools, we can see this

1 | Dumps the seccomp BPF from an execution file. This work is done by utilizing |

And we have a ptrace syscall in our binary, which is obviously causing the issue - so let's patch that out.

Now running seccomp-tools:

Bingo!

But one thing we have to keep in mind, is the loop in which seccomp is being called. Note that it is not just one filter being set, it is eight of them.

v0 is acting as the loop constraint here, making it run for 8 times, meaning 8 filters being set.

To dump all 8 filters, we can use the -l flag with seccomp-tools.

And to clear out all the other garbage being printed along with the output, we can use a little bit of bash.

1 | seccomp-tools dump ./chal -l 8 | grep -v "=======|CODE" | cut -d" " -f7- > disasm.txt |

Now that we have all 8 filters in a single file, time to solve for the constraints.

# Solving the challenge

Looking at the file (and from the challenge, too), we can see that we'll have 6 QWORDS to input, which it checks and returns KILL if it's wrong and ERRNO(0) if it's correct.

First thing that comes to mind is z3, so let's go for that.

Here is my script to parse the file and add constraints and "emulate" the filter on my args

1 | from z3 import * |

That's one way to solve it, but one way doesn't cut it, does it?

After the CTF, I came across Klee. Klee, you could say, is a Symbolic Virtual Machine (Solver), that allows you to symbolically execute a C source file. This is advantageous for 2 main reasons:

- You don't have to bother about having to convert C source to Python (to have to apply Z3 on it to solve symbolically)

- While converting from C to Python, we don't have to worry about stuff like signedness and typecasting 😃

Klee is a symbolic execution engine that explores program paths symbolically, treating variables as symbols rather than with concrete values. It is built on top of the LLVM compiler infrastructure, so this integration allows it to work easily with programs written in C/C++, and leverage LLVM capabilities for program analysis and transformation.

# Install Klee

Install Docker (since that is what I used to run Klee on this)

1 | docker pull klee/klee |

# Convert C source to Bitcode

(Bitcode is the format of code that Klee operates on. It is the LLVM IR representation of the code used by compiler chains like clang )

1 | clang -emit-llvm -c <filename>.c |

This will generate a directory with a number (indicating the number of times you've run Klee on the file so far), klee-last is the directory with the information on the file that was last symbolically executed with Klee.

1 | ls klee-assert/ | grep assert |

The files are output in a format test<number>.assert.err .

To run Klee on your C-source, simply run

1 | ktest-tool klee-last/test<number>.ktest |

To generate the filter.c files to run using Klee, you can do the following:

1 | seccomp-tools dump ./chal -l 8 > full_disasm.txt |

<br>

Followed by a script to split these files and parse them, then convert them to C files in the format the Klee expects

1 | # split the large output into 8 separate files properly |

All in all, this was a very fun challenge for me to solve - with lots to learn. GGs to the author from IrisSec for making such a unique challenge!